2014/09/28

Milano – lavoratori in coabitazione/a workers’ cohousing

Casa Bru

Silvia Sitton

Mangiamo un eccellente risotto ai radicchio rosso seduti intorno a un tavolo di legno di quelli lunghi e stretti con le panche ai lati che ci sono anche all’Oktoberfest. La spesa ognuno la fa per sé, però la sera si mangia insieme a Casa Bru e nessuno ha rimostranze sul menù, chi cucina non si aspetta ringraziamenti e neppure chi lava i piatti. La suddivisione naturale e l’alternanza spontanea dei compiti funzionano, e per il resto bisogna adattarsi. Non ci starebbe male una scritta del tipo “vivi e lascia vivere” sul portone di Casa Bru, dove l’abitare è anarchico e democratico allo stesso tempo.

Andrea, che ha cucinato, mangia a gambe incrociate sul divano dietro di noi, indosso una t-shirt bianca tagliata bene con la stampa di un teschio che gli lascia scoperte le braccia tatuate.

Condivido il tavolo con la mia amica Elisa che mi lascia il suo letto per la notte, Alessandro e Filippo che finito il risotto spariscono in una delle camere a comporre drum&bass, ed Eugenio che, come Filippo, a Casa Bru non ci vive, ma, quando non è in giro a recuperare sciami di api, ci capita spesso.

Non c’è Giorgio che di mestiere fa lo street writer e adesso è Roma dove lo hanno chiamato a fare un muro. Arriva invece Elia, vestiti e atteggiamento alla Fonzie che di mestiere insegna storia all’università e che a vederlo non diresti mai che è uno del collettivo Zam, un centro sociale che a Milano è un’istituzione. Saluta con le mani nelle tasche del giubbotto di pelle, si prepara un piatto di pasta sempre con le mani in tasca e appena finito scompare, ancora con il giubbotto addosso.

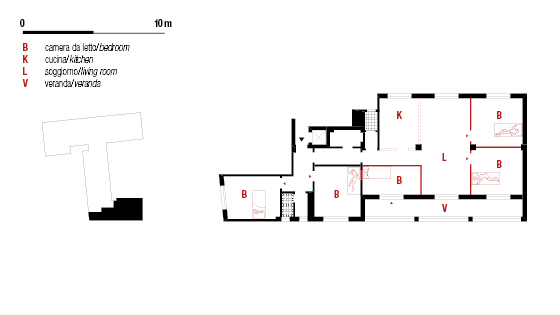

In questo appartamento dall'atmosfera berlinese con vista sulla stazione centrale e su un trittico di ciminiere spente ci vivono in cinque, ognuno in una camera che costa 430 euro al mese, che in tutto vogliono dire 25.800 euro all’anno che il padrone di casa si mette in tasca. Il padrone è proprietario di tutto l’edificio, dai campanelli direi almeno una cinquantina di appartamenti, tutti in affitto, che a fare il conto di quanto possono fruttare uno si spaventa.

Mentre la musica in sottofondo sale di intensità e l’orologio passa le dieci, Andrea esce per andare ad un concerto, qualcuno dice in taxi, che fa molto punk-chic, e mentre chiude la porta di camera sua intravedo una libreria piena di vinili, un pianoforte e di fianco una batteria. Di giorno Andrea si occupa di post produzione video mentre la sera cura una trasmissione radio di musica hardcore e quando è libero si va a vedere un concerto. È il coinquilino più anziano e mi pare di capire anche il padrone occulto di Casa Bru, quello che decide dove appendere un poster, se spostare i divani e quando bisogna pulire; non sembra un padre padrone però, ha gli occhi sensibili e i modi gentili, azzarderei sangue nobile nelle vene, sotto all’inchiostro punk che gli decora le braccia.

Immagino abbia dato lui l’autorizzazione per il concerto casalingo della band di ska-jazz di Alessandro qualche domenica fa, che ha radunato un centinaio di persone a Casa Bru, senza che nessuno dei vicini si lamentasse, forse perché la signora del piano di sotto è sorda o forse perché per molti di quelli che abitano lì un concerto non è più rumoroso della vita quotidiana.

Una ricerca di qualche anno fa ha stimato che a Milano siano oltre 22.000 i lavoratori che vivono in co-abitazione, un modello abitativo che permette di condividere non solo il costo dell'affitto, ma anche le spese condominiali e gli importi delle bollette.

Con la crisi economica, da fenomeno prettamente studentesco, la coabitazione si sta diffondendo sempre più anche tra lavoratori, costretti a spostarsi da una città all'altra per inseguire un lavoro con il quale è sempre più difficile riescano a pagarsi l'affitto da soli. Se da una parte nella maggioranza dei casi sembra una scelta forzata, dettata da ragioni economiche, dall'altra sempre più spesso condividere la casa con altri si trasforma in qualcosa di voluto, a cui ci si aggrappa per contrastare l'isolamento tipico delle grandi città.

A Casa Bru basta sedersi sul divano arancione affacciato sulla grande veranda piastrellata in fucsia e nero che arriva sempre qualcuno con cui fare le chiacchiere, fumare l’ultima sigaretta della giornata, ridere e piangere tra gente che va e gente che viene.

Casa Bru

Silvia Sitton

We eat an excellent risotto with radicchio sitting at a long and narrow wooden table with benches on both sides, just like those of the Oktoberfest. Each cohabitant shops for himself, but the dinner is shared and all people eat together at Casa Bru: no complaints about the menu, no thanks for the cook and the same for whoever washes the dishes. The natural sharing and the spontaneous turnover of tasks work well, and for everything else you have to adapt. On the front door of Casa Bru it would be nice to have a motto such as “live and let live”: in this house, living is anarchic and democratic at the same time.

Andrea, the chef, is eating cross-legged on the couch behind us, a white t-shirt with a skull press on, which leaves exposed his tattooed arms.

I share the table with my friend Elisa – who will host me in her bed for the night –, Alessando and Filippo – who disappear in one of the rooms to compose drum & bass as soon as they finish their risotto –, and Eugenio – who, just as Filippo, doesn't live at Casa Bru but is often here, at least when he is not around to save a bee colony.

Giorgio, a street writer, is not here tonight: he is in Rome to work on a wall. Instead, here comes Elia, same clothes and attitude as Fonzie, who teaches history at the University of Milan. It can be difficult to imagine him as one of the members of the collective Zam, a social centre which is an institution in Milan. He says hello without taking his hands out of the leather jacket pockets, he cooks a pasta dish for himself, always his hands in his pockets, and disappears just after it’s finished, his jacket still on.

The cohabitants of this flat with a Berlin atmosphere and with a scenic view of the central station (complemented by three abandoned chimneys) are five. Each room costs 430 euro per month, which amounts to a total 25.800 euro per year easily gained by the landlord. The landlord owns the totality of the condominium, at least fifty apartments judging from the bells, all of them rented – just thinking how much he can earn from this makes me scared.

As the background music increases its intensity and the watch marks ten o'clock, Andrea comes out to go to a concert, someone says by taking a taxi, which is very punk-chic; while he closes the door of his room, I can glimpse a library full of vinyls, a piano and a drum set. During daytime Andrea works in the video post-production sector, while in the evening he looks after a radio broadcast of hardcore music and when is free, he often goes out to see a concert. He is the oldest cohabitant of Casa Bru and he also seems to be the hidden master of the house, the one who decides where to hang a poster, where to move the couch or when it is time to clean. However, with his sensitive eyes and gentle manner, he does not look like an authoritative father – there must be, I guess, aristocratic blood under the punk ink dressing his arms.

I suppose it must have been Andrea to give permission for the house gig of the ska-jazz band of Alessandro that was given a few Sundays ago at Casa Bru. More than a hundred people attended that evening, with no trace of complaints coming from the neighbours, possibly because the lady living downstairs is deaf or possibly because for most of the people living in the building a concert is not noisier than their everyday life.

A research of some years ago about students and workers living in Milan estimated that over 22,000 workers shared their house with other workers, to save money non only from renting but also from the service charge and the bills.

With the economic crisis, cohabitation, which was initially mostly a student phenomenon, is spreading more and more among workers, who forced to move from one city to another to go after a job that often doesn’t allow them to rent a house by themselves. While in most cases this seems to be a forced choice, imposed by economic reasons, on the other hand sharing the house with other people is increasingly becoming a intentional choice, a way to contrast the alienation that is typical of big cities.

At Casa Bru you can just sit on the orange couch in front of the large, pink-and-black-tiled veranda, and someone will always be there to chew the fat, smoke the last cigarette of the day, laugh and cry among people who go and people who come.

Guarda l’intervista in HD su Youtube/Watch the interview in HD on Youtube

№ 6/21

№ 1/1

Next project: → Senigallia – “Vivere Verde”/”Green Living”

Previous project: ← Milano – ospitalità domestica/home hospitality